(Notes on Time, Loss, Art, and Carrying On)

The One About How It Looks

Age alters the surface of us long before it touches the core. The body bends, lines deepen, and the mirror insists on change, yet inside we remain strangely untouched. Like Dorian Gray, we carry a quiet constancy through the years, carrying within us a youth that time cannot quite persuade to grow old. Oscar Wilde once said temptation yields only when embraced; time, however, is less forgiving. It leaves its mark on the skin but spares the hidden life within. Memory holds back decay, desire still speaks in its first voice, and the self continues to stir beneath the wear of years. As Yeats wrote, the body may become “a tattered coat upon a stick,” but within it lives an undiminished spirit, still listening to familiar longings, still dreaming familiar dreams, and still astonished at how swiftly the years have slipped away.

Einstein’s theory of relativity fundamentally changed how we understand time. Rather than being absolute and the same for everyone, he proved that time is relative, passing at different rates for observers moving at different speeds. He said, “The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” It makes sense, then, that for me, 1985 and 2025 exist simultaneously, that my memories of both, and all the time between, merge into one continuum, and that it all, truly, feels like yesterday.

A quarter of a century has passed since the spectre of Y2K dissolved at the stroke of midnight, and yet it seems we learned little from that collective misapprehension, least of all about how pliable our fragile minds remain. We are still bent easily by market forces, by the Midas touch of shiny new things, spun endlessly on the great wheel of misinformation that instructs us whom to love, whom to hate, how to think, and what to fear. Even now, in this post-apocalyptic age, having endured The Virus and lived to tell the tale, we persist as obedient consumers, disciples not of wisdom but of accumulation. Richard Ashcroft was right. “It’s a bittersweet symphony, this life. Try to make ends meet, you’re slave to the money, then you die.”

Growing older has proved far gentler than I once imagined, less an erosion than a quiet return. It feels like a long, unplanned journey, taken without a destination, only to arrive at oneself, steadier, clearer, quietly at ease. There is comfort in this season, a stoic contentment born of having outlived youthful follies and the endless churn of changing scenes, and of being released from the exhausting labour of pretence. Growing up may be a torrential storm, but I can see clearly now the rain is gone.

The Name is Mamdani

After two years of unrelenting witness to the cruelty unleashed on Gaza, a slow unveiling of humanity at its most callous, and a year marked by the passing of great men and women, loss piled upon loss until the spirit felt close to exhaustion. And yet, even then, the heart found itself unexpectedly warmed by a fragile flicker of hope. Beneath the swell of moral regression and the relentless noise of depravity echoing across the world, there are still small, luminous acts, hidden veins of light still pulsing beneath the surface.

In an age when world leaders no longer bother to conceal their contempt for civil rights, when power is pursued with naked greed and the hard-won achievements of the past century are casually dismantled, moments like the election of Zohran Mamdani in New York cut cleanly through the armour of cynicism. They remind us that the force of good people choosing what is right, even against the full weight of entrenched power, has not been extinguished. And in those moments, even when such a victory in a distant place alters nothing in the mechanics of one’s daily life, one recognises that belief in justice and conviction is not naïveté, but a deliberate, defiant refusal to allow despair to dictate the limits of what remains possible.

We have lived through a ceasefire that is no ceasefire at all; a twelve-day war with Iran that flared and vanished like a warning shot; executive decrees spilling from the White House; and missiles striking Doha. We watched Gen Z youthquakes in Nepal, Kenya, Madagascar, Morocco, Indonesia, Peru, and the Philippines, even as a massacre unfolded in Tanzania and famine hollowed Gaza to the bone. The earth itself seemed restless, nature reminding humanity of its limits: an earthquake in Tibet, wildfires devouring California, a long-dormant volcano stirring awake in Ethiopia, a catastrophic hurricane tearing through Jamaica, severe heatwaves in India, and devastating floods in Southeast Asia. History bent in strange directions: an American pope elected, killings grinding on in Sudan and Ukraine, a G20 summit convened on African soil, and an attempted coup in Benin. All the while, ships stalled in the Red Sea, artificial intelligence leapt forward faster than our ethics could follow, democracy retreated in plain sight, and a climate summit convened in the Amazon as the world continued to burn.

We lost them one by one, and then all at once, a constellation dimming across faith, politics, music, film, literature, and sport. The Aga Khan, Pope Francis, Brian Wilson, Frederick Forsyth, Edmund White, Sly Stone, George Foreman, Gene Hackman, Roberta Flack, Marianne Faithfull, David Lynch, Ozzy Osbourne, Hulk Hogan, Robert Redford, Diane Keaton, Jimmy Cliff, Dharmendra – lives that shaped how we prayed, how we imagined, how we fought, how we sang, how we told stories to make sense of the world. Each departure felt like the closing of a chapter, the end of a particular cadence of courage, rebellion, tenderness, or grace. And then there was Raila Odinga, whose life belonged not only to history but to unfinished conversations about this country’s justice, dignity, and the long, stubborn arc of democracy.

What remains is not absence alone, but inheritance. These great men and women leave us melodies that still find us in our quietest hours, words that continue to sharpen our conscience, images that remind us what beauty once looked like and could look like again. We grieve them because they mattered. We give thanks because they gave so much. In their work, their risks, their defiance, and their generosity, they handed us something enduring, proof that a single life, fully lived, can widen the world for those who follow.

This year, I lost a personal hero, the great senior counsel, Pheroze Nowrojee, a mentor, teacher, poet, friend, and one of the most beautiful human beings ever to grace my life. His passing left an ache that words struggle to carry. He embodied, with rare integrity, every moral principle one hopes to find in a human being – an unwavering commitment to truth, honour, and justice. A gentleman in the truest sense, who lived his values rather than proclaimed them.

Pheroze showed us, through both his work and his way of being, the quiet but formidable power of the law to dignify lives, to protect the vulnerable, and to lift those most in need. His faith was not loudly worn, but gently visible, in his eyes, in his generous smile, and in a humility that shone like a torch in a tunnel.

It is said that one should never meet one’s heroes. I now understand why. Because no one prepares you for how devastating it feels when you lose them.

The Books: The Twists and The Tales

The Rest of Our Lives by Ben Markovits is one book that has stayed with me this year, not because I could in any way relate to the narrator’s journey, but because of how it carried the naked honesty of the ordinary, the way life insists on its own unplanned course, indifferent to our careful maps and ambitions. In its pages, a middle-aged man looks back on a lifetime marked by service, duty, and disappointment, and what emerges is not bitterness but a quiet reckoning with the things that endure, the fragile threads of love, the dignity of small acts, the stubborn pulse of hope. It is not a story of triumph, but of the simple clarity of what remains when everything else has fallen away.

The Booker-winning Flesh by David Szalay is a story that puts the primacy of the body front and centre as it traces the rise and fall of a man whose inner life remains opaque throughout. He approaches his life as a series of detached events, but his most formative experiences, a moment of physical fearlessness, an intense affair, reverberate, even as he finds himself unable to account for his bursts of violence and desire.

In The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (And His Mother) by Rabih Alameddine, a man in his sixties navigates life in Beirut, living with a mother whose personality is as volatile as Lebanon’s perpetual political turmoil. The narration is relentlessly funny, even as it turns to the dark and disturbing events of his past.

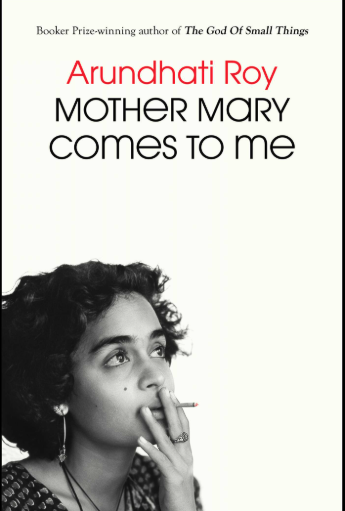

The two books I return to most insistently this year are both works of non-fiction. The first, Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy, is a memoir shaped around her mother, but it is also an excavation of the political and social forces that fashioned the writer, and, with them, her capacity for love, anger, and radical empathy. Arriving nearly three decades after The God of Small Things, the book reads like a necessary companion to that singular novel, a quiet unlocking of the world that made it possible. In tracing the intimate and the ideological side by side, Roy does not explain so much as illuminate, allowing us, at last, to glimpse the life and history that breathed her masterpiece into being.

The second is One Day Everyone Will Have Been Against This by Omar El Akkad, a searing and morally urgent work for anyone who has lived through the past two years of the Gaza war and emerged disoriented by a world that feels at once heartless and helpless. The book confronts the reader with the slow, almost imperceptible normalisation of atrocity, tracing how states, institutions, and ordinary citizens learn to tolerate, and then justify, acts of despicable violence committed in their name. With grave clarity, El Akkad asks how future generations will read this moment, what they will make of our silences, our evasions, our carefully constructed rationalisations, and whether moral reckoning becomes unavoidable once history finally renders its verdict.

These are my favourite books of 2025:

- One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This OMAR EL AKKAD

- Mother Mary Comes To Me ARUNDHATI ROY

- The True True Story of Raja the Gullible (and His Mother) RABIH ALAMEDDINE

- The Rest of Our Lives BEN MARKOVITS

- Seascraper BENJAMIN WOOD

- Flesh DAVID SZALAY

- The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny KIRAN DESAI

- Mothers and Sons ADAM HASLETT

- The Land in Winter ANDREW MILLER

- Theft ABDULRAZAK GURNAH

My Top 10 Books of 2025

The Screen: An Imitation of Life

In his Poetics, Aristotle argues that art (especially poetry and drama) is a form of mimesis, the imitation or representation of human actions, emotions, and nature. For him, art does not merely copy reality mechanically; it interprets and reveals more profound truths about life, character, and moral choice. Oscar Wilde famously inverted this idea, claiming that “life imitates art far more than art imitates life.”

We live in a cultural moment hungry for catharsis, for breaking free, even momentarily, from a world caught in a frenzy of eating itself and the destiny that awaits it.

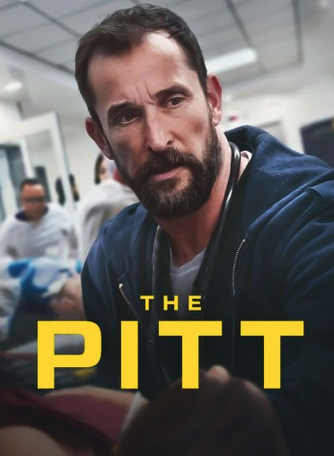

It has been a tremendous year for film and TV, with directors and screenwriters satirising and dramatising the full spectrum of existence in this age. The HBO Max series, The Pitt, is likely one of the finest TV shows of recent years, dramatising the events in a hospital emergency room over a 24-hour period, and managing within that timeframe to explore the impact of prolonged exposure to trauma, scarcity, and impossible choices. The characters arrive with social histories shaped by poverty, violence, addiction, immigration status, and neglect, showing us how heroism today lies in endurance rather than triumph.

Season two of Andor feels like the quiet fulfilment of a promise long deferred to those of us who have lived with Star Wars for decades. It strips the saga of mythic comfort and replaces it with something rarer and braver: an unblinking attention to how rebellion is actually made, through fear, compromise, fatigue, and moral cost. As a lifelong fan, I found in it a deeper fidelity to the spirit of the galaxy than lightsabers alone ever provided: the sense that hope is not inherited, but built painstakingly by ordinary people who choose resistance again and again, knowing the price.

In film, we have had outstanding acting performances that would justify a photo finish to the Oscars next year. In One Battle After Another, Leonardo DiCaprio brilliantly plays a man worn down by years of ideological struggle, someone who has fought for causes that once felt urgent and righteous, only to find himself haunted by compromises, betrayals, and the slow corrosion of certainty. In Blue Moon, Ethan Hawke gives one of his most powerful acting performances as Lorenz Hart, the brilliant, wounded lyricist of Rodgers and Hart, caught on the night when his creative partnership, and his place in the world, is slipping away. Enriched by one of the year’s best film dialogues, he plays a man undone by his own sharpness, remaining funny, caustic, needy, and acutely aware that history is passing him by. And in Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, Jeremy Allen White perfectly plays Bruce Springsteen at his most inward, during the making of his Nebraska album in 1982, when fame had arrived, but clarity had not. He presents an artist wrestling with depression, obligation, and the fear that success may cost him his honesty.

Four International Films stood out for me this year. The first, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, is a darkly comic film that unfolds in the aftermath of a death within a Zambian family, using ritual, memory, and silence to expose the violence buried beneath respectability. The French-Iranian film It Was Just an Accident turns an apparently minor incident into a quiet moral reckoning. The film examines how authoritarian systems and the people living within them rely on euphemism, silence, and “accidents” to evade responsibility, revealing deeper layers of fear, guilt, and complicity, as the characters negotiate survival in a world where truth is dangerous, and accountability is optional. The third film, Late Shift, is a tightly observed Swiss drama that follows a hospital nurse over the course of a single night shift, as understaffing, exhaustion, and institutional pressure push her towards an irreversible moral crossroads. It is a haunting portrait of care under strain and of how systems quietly transfer their failures onto individuals’ consciences. And lastly, the Indian drama, Homebound, follows two childhood friends from a marginalised community in rural northern India whose hopes for dignity and belonging are bound up in their pursuit of government jobs. Set against the country’s social hierarchies and the Covid pandemic, the story examines friendship, ambition, and betrayal as the promise of upward mobility exposes the fragility of loyalty under pressure.

These are my favourite films and TV shows of 2025:

Films

- One Battle After Another

- On Becoming A Guinea Fowl (Zambia)

- It Was Just An Accident (France/Iran)

- A House of Dynamite

- Homebound (India)

- Late Shift (Switzerland)

- Blue Moon

- Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere

- Sinners

- F1: The Movie

TV

- The Pitt (HBO Max)

- Andor, Season 2 (Disney+)

- Mobland (Paramount+)

- Dept Q (Netflix)

- Severance, Season 2 (Apple TV+)

- Shaka Ilembe, Season 2 (Mzansi Magic/M-Net)

- Slow Horses, Season 5 (AppleTV+)

- This City is Ours (BBC)

- The Bear, Season 4 (Hulu/FX)

- Adolescence (Netflix)

My Top 10 Films of 2025

The Music: The Sound and The Fury

Spotify, that oracle of streaming that gives us sprawling libraries of sound, politely dropped its annual number in early December, claiming that my sonic soul was 56. My first fleeting thought was how mistaken it must be to have me years wrongahead, but on second reflection, I realised the algorithm couldn’t have been more accurate. Though I still chase newer sounds and newer artists, my playlists are a testament to a golden age. To a time when music sprouted with harmony and poetry, discovered, like new friends, in borrowed mixed tapes that were played and circulated in every household in the neighbourhood, like a public bus doing the rounds. I grew up listening to real artists who played real instruments, crooning original verse that pre-dated the reign of Autotune, sampling, and AI. I may not be 56 (yet), but I feel as old Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Sultans of Swing. And that’s a badge of honour for musical purism.

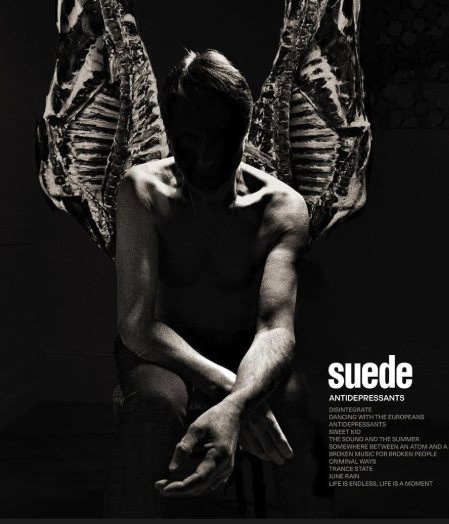

It hardly needs saying that the music I have been drawn to this year is steeped in reverb and haunted by the retro textures of the 1980s and 1990s. Suede’s Antidepressants captures the 90s band not ageing into comfort, but arriving at a harder-earned clarity, one shaped by the demands of emotional survival in middle age. Shot through with jagged post-punk guitars and surging choruses, the album becomes a portrait of refusal, a band rejecting numbness and choosing instead to feel everything – pain, desire, rage, and fleeting hope – even as relief is chemically promised and existentially uncertain.

In July, I was fortunate to discover Nation of Language (thanks to that all-knowing Spotify algorithm) and their new album, Dance Called Memory, a record that could easily have been made in 1983. It is rich with pulsing analogue synths, crisp drum machine, and lyrics preoccupied with time, loss, and how memory reshapes intimacy.

If, like me, you came of age on the pulse of 1990s alternative rock, this year has felt like an unexpected homecoming. Stereophonics, Razorlight, and The Fray have returned not as relics trading on memory, but as artists newly alive to their own craft, releasing songs that rank among the finest of their careers. This is no indulgence in nostalgia, nor any overstatement. It is the rare pleasure of hearing familiar voices speak with renewed purpose.

And, inevitably, the year’s coolest song is Tame Impala’s Dracula, a distillation of pop’s timeless pleasures, refashioned with a sharper edge. It carries the sweep and immediacy that have always made pop irresistible, but wears them now with the piercings, ink, and self-aware insolence of a Gen Z sensibility, glossy and dangerous in equal measure.

These is the favourite music of 2025:

Albums

- Antidepressants SUEDE

- Glory PERFUME GENIUS

- Virgin LORDE

- Critical Thinking MANIC STREET PREACHERS

- Dance Called Memory NATION OF LANGUAGE

Songs

- Sugar High RAZORLIGHT

- Dracula TAME IMPALA

- My Heart’s A Crowded Room THE FRAY

- Disintegrate SUEDE

- Songs I’d Rather Not Sing THE FRAY

- Seems Like You Don’t Know Me STEREOPHONICS

- I’m in Love JELANI ARYEH

- Ordinary ALEX WARREN

- moody ROYAL ETIS

- Catching Feelings CHRISTINE & THE QUEENS

My Top 10 Songs of 2025

The One About How It Feels

And so another year slips past, and like the civilisations that rose and fell before us, we find ourselves still struggling to understand how progress and regression, like the relativity of time, bend and coexist within the same fragile moment. We know more now than any generation that preceded us. We have dismantled the old fictions that once divided humanity by race, gender, and creed. And yet we continue to wage war on a scale so vast it feels biblical, killing one another with an ancient fervour, as though we had only just stepped out of the pages of the Old Testament.

It feels as though the earth is suspended in an interregnum, caught between endings and beginnings, enduring either the labour pains of a new birth or the ominous swell before another great flood. Hindu mythology speaks of Shiva, whose eternal dance as Nataraja embodies this relentless rhythm, creation and preservation entwined with destruction, concealment, and grace, all unfolding at once. I sense that rhythm now, the heavy pregnancy of possible renewal, as we remain, stubbornly and beautifully, human, biting forbidden fruit, salvaging deathless love, and accepting our banishment from the garden of simple moral certainty. We make music from the thunder of falling bombs. We write our stories, stage our absurdities, and bear witness to ourselves, reminding one another, again and again, that empathy and compassion are the only hands that can pull us from the rubble. That love remains the only beauty to measure all beauties by.

I write to remember, because age alters the surface of us long before it touches the core. In the solace of interiority, I return year after year to the page, shaping a future out of stubborn, necessary hope. No matter how dark the world becomes, we have always reached for music, for literature, for the performing arts, not as escape, but as illumination, to steady ourselves, to tell our stories, to sing our songs, and to remind one another that we are still here, and that we must carry on regardless. The sea may be exhausted, its waters heavy with history and loss, yet it continues to ebb and flow, faithful to its ancient rhythm. And so, too, do we persist, writing ourselves forward into whatever light remains. An abject refusal of despair, and the belief that something essential survives intact beneath history’s damage.

“One day the killing will be over, either because the oppressed will have their liberation or because there will be so few left to kill. We will be expected to forget any of it ever happened, to acknowledge it if need be, but only in harmless, perfunctory ways. Many of us will, if only as a kind of psychological self-defence. So much lives and dies by the grace of endless forgetting.” – Omar El Akkad